“This was published first in the Washington Post electronically on 7/29/2017 and will come out in print this Tuesday. Click here for the link. The comments so far in the paper have overall been quite emotional and angry in their response. I am happy to discuss in more detail here on the blog and welcome any input or thoughts. But the responses in the Washington Post highlight to me why we need to not only have more questions with our families on issues of end of life but to have more depth to them as well.”

The dilemma for the critical care team was not uncommon. An elderly patient in the midst of a life threatening illness and in severe pain, not understanding the critical nature of their current situation. A decision needing to be made about how aggressive to be. A doctor trying to convince the patient to pursue a rational approach, one based on understanding the limits and capabilities of life supporting interventions. This situation plays out in ERs and ICUs across the country hundreds of times a day. But two key factors made this situation unique. First, this elderly patient struggling to breathe, battling low blood pressure and in a tremendous pain was my wife’s grandfather. Second, the doctor recommending aggressive life supporting measures, contrary to the limits set by his advanced directives, was me.

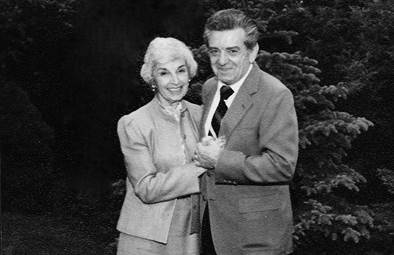

Fourteen years ago, Herb Lee, a healthy, independent 87 year-old, had been out to dinner the evening prior. Something must have been wrong with the food as he vomited all night long. In the emergency room the next morning, doctors diagnosed severe pneumonia complicated by shock and kidney failure. His breathing was labored, his oxygen was low and his pulse was fast and weak. But Herb was unable to process any of this. His sciatica had decompensated from lying on the hospital gurney. The only thing he wanted was pain medicine, and he wanted it now. But none was forthcoming given his tenuous blood pressure and marginal breathing.

Prior to this, Herb had been clear. After watching his wife battle metastatic cancer years ago, he knew what he did and did not want. No life support. No breathing machines.

This left Herb and his doctors in a bind. The medical team wanted to treat Herb’s pneumonia and sepsis. But antibiotics take time, often forty-eight hours, before they have an effect and patients often get worse before they get better. The pain medication he was desperately calling for at the moment was off the table as it would lower his blood pressure and decrease his breathing, two things he was struggling to do adequately.

The medical team was failing Herb on all fronts. Not only were they not giving him the best chance to survive, but allowing him to continue on in significant pain while struggling to breathe was unacceptable.

He was in no condition to think about and process complex life and death decisions.

So my wife’s family looked to me, having finished my training in internal medicine and pediatrics and now in my second year of Pulmonary and Critical Care fellowship, to help make decisions.

What do you do when you disagree medically with a patient on matters of life and death? When there is no ability to have a thoughtful, patient, nuanced conversation over life support. For Herb, was it a “hard no” to any intubation? Were two days ok if there was a high likelihood of recovery? Or was even one day too much? When doctors disagree with patients and families, it is usually the family choosing aggressive care in the face of overwhelming illness, where the benefits of life support are negligible or non-existent. It gives a reprieve of sorts, allowing for further discussion. But what if the patient’s decision leads to a potentially premature or unnecessary death from a treatable illness? What if a patient’s limits were stated without ever considering the current context? What if this is your own family member writhing in pain, struggling to breathe?

We often talk about decisions of life and death, of aggressive care or comfort, of full code versus DNR/DNI. Opposites. One or the other. Binary options. But in real life, applying these decisions can get messy. There is nuance and context and uncertainty. And what happens when, in these shades of gray, this fog, you disagree with your patient? What if you are a knowledgeable critical care doctor, and it’s your family member? If you choose to treat, you take away his autonomy and right of determination. If you choose to limit care, you are choosing an irreversible path to death and a future full of what ifs. What do you choose when you are in the fog?

I chose to treat, not to limit. I chose paternalism over autonomy. I chose a time-limited trial over a morphine drip. I chose not to be the grandson-in-law who made the last decision leading to Herb’s death. He had pneumonia. It was treatable. Reversible. Curable. I didn’t know if he had ever envisioned this, but I hoped I would eventually have the opportunity to ask him.

A breathing tube was placed. Morphine was administered to treat his pain. We bought some time to allow antibiotics and his immune system to turn the tide on his pneumonia and sepsis. At forty-eight hours he made enough progress to push forward another day. The breathing tube was removed 24 hours later and he was able to leave the ICU shortly thereafter. He avoided most, if not all, of the potential complications and pitfalls that often plague patients in the ICU. A week on the medical floor was followed by a transfer to a subacute nursing facility for more rehab. Eventually he was able to go home, back where he started.

In my world of critical care, this is a win. It does not get much better than halting the progress of a life threatening illness, supporting the body while it heals, and nursing the patient through a hospitalization, and ultimately returning home.

Over the next few months Herb would see another great grandchild born and celebrate family birthdays. And at one of those dinners, sitting next to Herb, I took the opportunity to finally ask…

“Herb, I made the right choice, right? Overriding your DNR?”

He looked at me and simply said, “I wouldn’t want to go through that again.”

He told me of the countless sleepless nights, lying in the bed, scared, confused, not knowing when light would finally come to end his darkness. It was hell and not one he wanted repeated. If he could do it over again, it would be no. No breathing tube. No life support.

I was shaken. What does it mean when an unequivocal win in my world is not a win in the eyes of the person for whom it matters most?

The intersection of critical illness, advance directives, and end-of-life decisions is an uncomfortable place. It is hard to talk about these issues when in good health much less in sickness. But we must run towards, and throw ourselves into, the discomfort. We need to talk to our family and friends and share what it is that makes life worth living. We need to explore what “quality” means for each of us. By doing so, we inject some much needed light into the darkness and the fog, and help bring clarity for when it’s needed most.

A few months later, Herb developed another severe pneumonia. There were no tense conversations, no anxious looks among family. There was light where before it had been dark. And as we focused on Herb’s comfort, that light remained. He died a few days later in the hospital, with the palliative assistance of hospice.

It has been more than 13 years since Herb passed away. Over that time, I have been involved in countless frantic discussions with patients and their families about goals of care in the midst of critical illness. It’s never easy, but because families often ask me what to do, I share with them Herb’s story. And by doing so, he continues to help shed light when it’s needed most and to help determine what a “win” means for each of us.