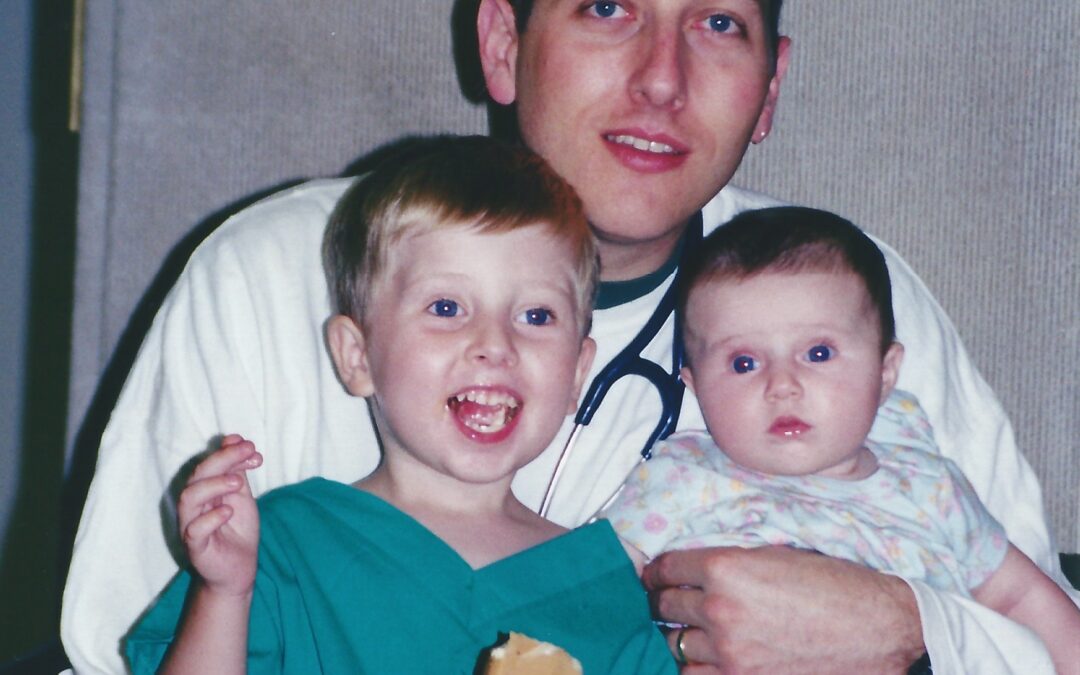

The day began the same as yesterday. As well as every day prior to that for the last few months. I was tired. Exhausted. The type of fatigue that envelops your brain in a dense fog, altering the way you see and hear the world around you. The type that impairs your ability to think clearly and process efficiently. It was the cumulative fatigue from too many nights of disjointed and ineffective sleep. My two children the culprits at home, my pager when at the hospital. The alarm clock told me it was 5:00 am and time to start moving. I was the senior resident on call for a busy general medicine service. I got ready mindlessly and drove to work, leaving my three-year-old son, ten-month-old daughter and pregnant wife behind.

The page from my wife would come a few hours later, while in the middle of hearing about a new admission. I called her back, expecting a generic morning update on the kids.

“I think I’m miscarrying.”

In my worn-out state, there was no reflexive response. Like the origin of a wave as a swell forms and the water gently rises, confusion first surfaced in my head. As the swell of emotions picked up momentum and power, sadness and feelings of loss crashed in. Then guilt over fleeting thoughts of being saved from even more sleepless nights another baby would bring. As the waves passed, I was left with loneliness. So far away from my wife at the moment when she needed, WE needed, to be together. I did something in that moment I had never done before. I called the chiefs and asked them to call in the resident on jeopardy to cover for me. Within a few hours, I was home at my wife’s side.

We sat together. We talked. We cried.

But as a few hours passed, the fact that someone else was covering for me caused increasing tension. Someone was doing my work for me. Admitting patients with my team, because I wasn’t there to do it. And as the sun set on the day, my wife turned to me and said, “It’s ok. Go back to the hospital. I’m alright.”

And I went back.

Thinking back to that moment, my stomach still twists in knots. How could I have walked away? How did the culture of medicine lead a fatigued, and emotionally exhausted, young doctor to leave his wife, who had just miscarried hours ago, to care for two young children on her own?

Did it start in medical school? Initial thoughts of self-doubt, and feeling like an imposter, slowly faded as we internalized subtle, and some not so subtle, comments from faculty. “You deserve.” “You belong.” We were told we were on a path to a higher and more noble calling, with great purpose and responsibility. Something bigger then ourselves. Whether from self-doubt or self-importance, we were driven to study. We spent hours reading and learning, dissecting and memorizing. We prepared for finals, mini-boards and shelf exams. And while doing so, our friends of old, no longer enmeshed in academic studies, enjoyed the perks and freedoms that came with new jobs and real incomes. We were too tired and too immersed in our narrowly focused world to connect with our friends. And as the dynamics started to shift in those friendships, we became a little more isolated.

Did it continue when we began our clinical rotations? The residents we looked up to as role models were always present and available. They taught us clinical pearls, ran codes confidently, and handled emergencies calmly. They were described as “strong.” So we emulated them, making ourselves present and available as well. For our assigned patients or a potential procedure. To be noticed. To be evaluated. To be appreciated. Those traits were deemed positive, earning merit. Never mind life outside the hospital walls. Reading a book for pleasure, enjoying a run along the lake, and being emotionally and physically available for our partners and children weren’t skills that made it into letters of recommendation.

Did it continue in residency? We took on more responsibility for our patients. Admit them, document them, draw their blood, administer antibiotics, check the labs, update their families, and plan their discharges. “To do” lists to be checked off before we could sign out and go home. In one month we would work twenty-six days. Seven of those were spent working overnight, non-stop into the next. Four days a month we were allowed to keep for ourselves. But those four days did not make up for being absent physically and emotionally for twenty-six. Not there to take out the garbage or help with laundry. A no-show for a friend’s birthday party. Too tired to take a turn rocking a child back to sleep in the middle of the night. Exercise or making a home cooked meal was off the table, when just keeping your eyes open for the car ride home from work was considered a win.

Did it continue in fellowship? Being on service or working in the clinic was not enough. There were patients to recruit for trials, night-classes to attend, and research to do. We needed to write another chapter and apply for another grant. That’s what our mentors and department chairs did. In the meantime, we weren’t there for our own children’s scarlet fever, chicken pox, recurrent strep throat, first steps and first words. What free time we had was spent moonlighting, as we tried to keep up with ballooning school loans, mortgages, and college savings for our kids.

At every step on the path to becoming physicians, the messages were clear. Be present. Be available. Leaving early was weak. The students, residents and fellows who stayed were dedicated and serious. Impressions were formed based on being visible. Evaluations were determined by our perceived dedication. But if, in the process of being ever present and available, we struggled to make it through the day, how could we be there for ourselves? To rest and recuperate. To think and process. And if not able to care for ourselves, how could we care for others?

It’s no wonder that in a 2015 JAMA systematic review, average depressive symptoms among resident physicians was 28.8%, ranging from 20.9% to 43.2%. In a similar article in JAMA 2016, the prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms among medical students was 27.2%, and the overall prevalence of suicidal ideation was 11.1%. And these numbers don’t address other mood disorders, such as anxiety, or the dysfunctional and harmful coping mechanisms of alcohol and drug use. It’s not surprising that there are so many struggling or failed marriages among physicians, as well as rampant burnout.

In medical school, we are taught about cells, tissues, organs and systems. We learn to write histories and perform physicals. We are preached to about antibiotics and anti-hypertensives. But where in the curriculum are we taught to care for ourselves? When in residency were we told to go home and make sure to be there for our families? When in fellowship was physician wellness placed on the same level as grant writing and lab techniques? Why is focus on family merely tolerated by our peers, instead of modeled and emulated? Too be fair, there have been a few mentors and role-models who showed us how to not only set appropriate limits and boundaries, but taught us that it was acceptable to protect our home lives from our work lives. But they have been outliers. Exceptions. Too often their solitary voices drowned out by the masses.

For too long, the culture of medicine has promoted this choice as binary. Spending time in the hospital to learn and care for patients versus spending time with our families. A zero sum game. But it doesn’t have to be. Why can’t there be a culture that promotes both? So far, attempts to normalize and humanize training have narrowly focused on specific issues such as work hours and work environment. But the culture of training new physicians also needs to change. Setting appropriate limits and boundaries, as well the concept of physician wellness, should be as prominent in the curriculum as human pathophysiology. We talk about developing the skills required to be a life-long learner in today’s internet-connected fast paced world. So too should we talk about promoting clinical excellence and dedication, but not at the expense of their families or their own happiness. Spouses and children should not bear the consequences of a flawed system.

There are only a handful of things in my life that, given another chance, I would do differently. My choice to pursue a career in medicine is not one of them. I love this profession and the unique opportunities it provides to help people in powerful and meaningful ways. But I do wish I could go back to that day during my residency when my wife miscarried. I wish I had stayed home with her.