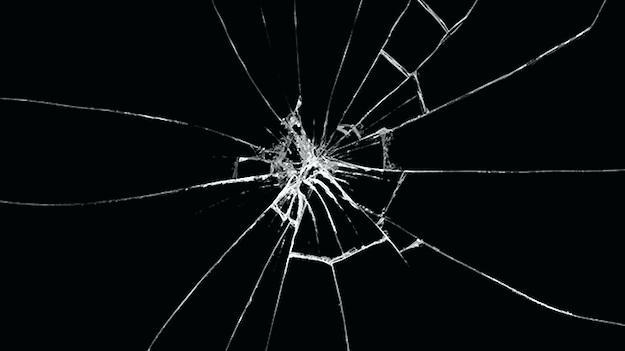

How do you know when someone is broken? When their spirit is fractured? When their sense of self no longer aligns with what once was. When you feel as if you have woken up in a foreign land, but that sense of displacement is coming from you, not your surroundings.

In television shows and movies, that moment for a doctor is obvious. The scene in which a physician cries in the stairwell, knees bent, head hanging dejectedly. A downward spiral into drugs and alcohol that leads to a near-miss in surgery. Or a final, explosive ranting monologue, that alienates the doctor in front of patients and peers. They have snapped. They have broken. At least until the next scene or episode.

Real life rarely follows a Hollywood script.

The slow burn of a physician breaking is usually far more insidious and is often masked by their own defense mechanisms and denial. Fatigue. Frustration. Irritability. Impatience. Complacence. Disconnect. Sadness. Anxiety. Anger. Depression. When something loved becomes something tolerated. When the excitement and potential of each new morning is replaced by the dread of what might lie ahead. Problems, that were once challenges to be solved, become roadblocks and barriers seemingly designed to thwart and frustrate. When it feels as though patients and staff are no longer expressing themselves, but are instead complaining and whining.

I do not consider myself a weak person. I have completed six Ironman triathlons. I finished the marathon portion of one after a bike crash left me with road rash covering the right side of my body. As a water polo goalie, I’ve had my eyelid split open and my nose broken. I survived four years of medical school and four years as a resident in internal medicine and pediatrics, enduring countless sleepless nights on call that were often calmer than nights at home with two young children. I asked my program for help only twice during that time. Once on the day my wife miscarried and once for the seventy-two hours after the birth of my daughter, our second child.

I pride myself on taking these challenges head on, and coming out standing tall and strong on the other side.

However, I was not immune from the cumulative burden and increasing stress that my life in medicine created.

Was it twelve years of highs and lows and the hectic pace in a private practice covering three busy hospitals and ICU’s? Was it working with a revolving door of hospital administrators, nurses, residents and medical students? Days filled with code blues, rapid responses, packed emergency rooms, understaffed floors and overworked nurses?

Was it the increasing size of my outpatient practice and the increasing medical complexities and call volume of my patients? Was it the increasing “obstructionist” insurance plans with the increasing number of prior authorizations to fill out and denials to protest?

Was it the never-ending documentation? Clicks required to satisfy the electronic medical record (EMR) or requests to modify charting to make sure diagnosis were “present on admission” or upgraded to the highest level of severity. Or documentation not designed to facilitate communication but to prevent potential litigation down the road.

Was it the stress of multiple impromptu and emergent family meetings for critically ill patients, rapidly synthesizing old documentation with new clinical information. Committing to an accurate and sound working diagnosis, while concomitantly initiating aggressive life-saving interventions. All while simultaneously and effectively communicating this crucial, but overwhelming, information to people I might be meeting for the first time?

Was it the frivolous lawsuit I was dragged into, by virtue of having been on call for the hospital that night? Or the multiple depositions I gave and read and reread, combined with more than four years spent anxiously preparing for a trial from which I was dropped without ever taking the stand?

Was it the challenges of being present and available for my family? Trying to support my children, whose lives grew more complex with age. Being present, but not intrusive. Being aware of, understanding and monitoring social media in a world of ever changing and shifting norms.

I found myself exhausted and tired. I became more callous, impatient and terse with my patients, residents and medical students. With my physician partners and nurses. With friends. With family.

At first, I failed to acknowledge what was in front of me. I’m just tired, or it’s the lawsuit, or we are short staffed, or I just need to get efficient with the EMR, or it’s the crazy flu season, or I just need to get to my vacation week and recharge. I wanted there to be a reason. A fixable external problem. Because if not, then maybe I needed to look internally. At myself.

Was I too weak? Was I not strong enough? Did I not have enough fortitude, endurance or “grit”? With those thoughts of weakness, came feelings of shame.

I started talking about taking a break or cutting back. I envisioned teaching at a high school and coaching water polo. I thought about going back to school to figure out different ways of using my knowledge and skills. I thought about spending more time with my kids and having the emotional and physical energy to be patient and present, not irritable and dismissive. I thought about writing on patients that had a tremendous impact on my life, of decisions made and opportunities missed, and the challenge of finding balance in my life.

And then instead of talking and thinking, I did.

I hedged a bit at first, cutting back to half-time with an option to return to the status quo after a year. I dipped my feet in the water. It felt cold and chilly on my toes, and I was not quite ready to dive in.

A few months later, I jumped all the way in. And as I made that leap, I felt weightless, a fluttering in my chest, like driving fast over a rise in the road.

It has been approximately nine months since I went part-time. I am still getting used to the feeling. More time, less income. More freedom, maybe not enough structure. I am wrestling with a number of things. Financial choices are harder. Retirement is less certain. But those fears are fading, as I adjust to my new normal. I am also adjusting my sense of self. My identity. Who I am. Before, I was a partner in a successful yet crazy, busy practice, providing for myself and my employees. I was a teammate with seven other doctors, taking on challenges as they came, just as I have my whole life. But now, I have to ask the questions; Am I no longer that partner, that provider, that teammate, because I failed? Was I not good enough? Capable enough? And if so, what does that say about me? What then am I?

Somedays, I just stop and reflect, writing in my journals. And I try to answer those questions. Who am I? I close my eyes and let my thoughts and recent actions fill the void.

I am a parent taking my kids on college visits. I am also a college applicant, applying to Hopkins School of Public Health and Policy, where I hope to start in the winter. I am a high school water polo coach working with an amazing bunch of teenagers. I am a water polo goalie for my Master’s team. I am a triathlete training for another Ironman this fall. I am a husband celebrating and tackling these mid-life challenges, together with my wife. And I am a part-time doctor who still loves the challenge and privilege of taking care of patients when they are at their sickest and most vulnerable.

I am not broken. I am just getting started.